Creditors

★★★★☆ Compellingly troubling

Royal Lyceum Theatre: Fri 27 April – Sat 12 May 2018

Review by Hugh Simpson

Strikingly staged and worryingly contemporary, Creditors at the Lyceum is unsettling and difficult to ignore.

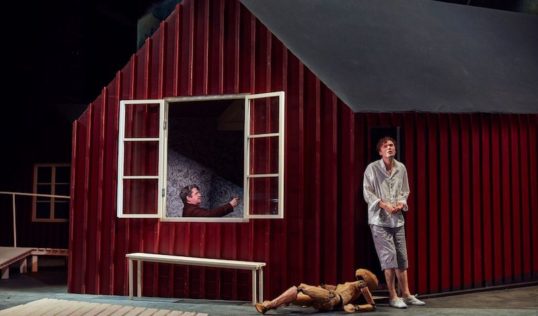

Strindberg’s unsparing portrait of human relationships features novelist Tekla, Adolph, an artist who is her second husband, and Gustav, whose advice to Adolph may not be as unbiased as he claims.

The play divides neatly into three separate two-handed sections, but the Lyceum have chosen to eschew any breaks. While this does strain the patience a little, the performance and staging are very strong indeed.

One would hope that the patriarchal assumptions of male characters from 1888 would have vanished long ago, but – just as the costumes and the set seem to straddle the 19th century and the present day – there is something horribly relevant about their concerns.

Both the men react badly to what they perceive as the erosion of their dominant position; Adolph through childish narcissism, Gustav through furious chauvinism. While the title suggests a calculating, profit-and-loss approach to relationships, the reality is that they are driven more by jealousy and pride.

That Gustav’s spitting-mad sophistry should be so recognisable is thoroughly depressing – no doubt nowadays he would have a massive following online and be interviewed on Channel 4 News. Stuart McQuarrie is horribly convincing, smooth exterior only just concealing the bile within.

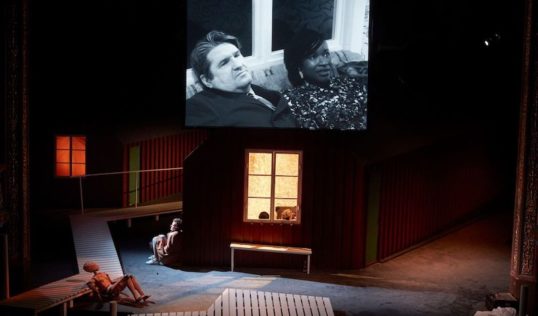

intimate

McQuarrie also deals excellently with an unexpected change of medium as his conversation with Tekla is played out on a huge screen. His film and TV experience show through as his expressions and gestures become much more intimate, mirroring the shift in emphasis in the character’s motives.

Good as McQuarrie is, there is a definite feeling that we are spending as much time in the character’s company as we could reasonably bear – which is something else an interval might have helped alleviate. The same is true in a different way of Adolph, whose idea of talking therapy seems to be saying the same things about yourself repeatedly and shouting down your partner if they disagree.

Edward Francis, however, gives the character a wounded quality that is extremely effective. His every movement is beautifully considered, while his habit of speaking in headlong rushes and gulps of air provides an impressive contrast to Gustav’s raconteurial misogyny.

Adura Onashile’s Tekla, apparently self-possessed but defining herself entirely by other’s reactions, is in a constant battle with herself and the society around her. Onashile is very good at showing the doubts and limitations that keep threatening to undermine the character’s outward grace.

nervous titter

David Greig’s adaptation – first seen in 2008 – has a modern bite that is extremely successful on the whole. There are, however, moments when it is less convincing. While billed as a ‘tragicomedy’, it does not seem terribly funny – many of the obvious ‘jokes’ revolve around someone saying something stupid about physical or mental illness, and provoke little more than a nervous titter.

Where the production does achieve immediacy, however, is in Stewart Laing’s arresting direction and design. It begins with Franklin emerging from a pool in swimming trunks in front of some oddly robotic Girl Guides, to a soundtrack of woozy hip-hop. If nothing that comes later is so surprising, it does set the tone. The odd perspectives of the set are constantly jarring, while Pippa Murphy’s sound design suggests that nature has a constantly toggling on-off switch.

There is one compelling moment, when Gustav reads a letter, where nothing appears to happen for a long time. This seems absurdist precisely because it is so realistic. Similarly, the movements of those recurring Guides, while only slightly heightened, come across as decidedly strange.

While it is Strindberg’s later plays that are often thought to be symbolic or surrealist, there is something odd going on here too. Love, hate and paranoia come seeping out of the characters, in a way that may be ridiculous but is also more real than we may care to admit.

Running time 1 hours 55 minutes without interval

Royal Lyceum Theatre, Grindlay Street, EH3 9AX

Friday 27 April – Saturday 12 May 2018

Tues – Sat evenings at 7.30 pm. Matinees Wed and Sat at 2.00 pm.

Information and tickets: https://lyceum.org.uk/whats-on/production/creditors.

Lyceum on Facebook: @lyceumtheatre.

Twitter: @lyceumtheatre.

ENDS