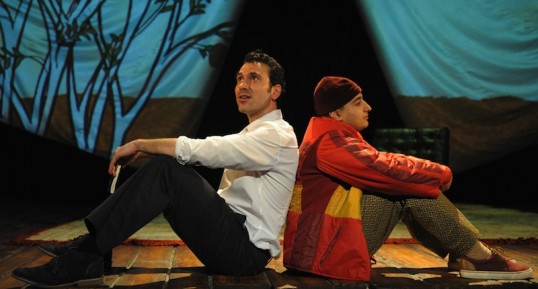

The Kite Runner

✭✭✭✩✩ Careful adaptation

King’s Theatre: Mon 10 – Sat 15 Nov 2014

Nuanced, emotional performances in the adaptation of The Kite Runner cannot fully compensate for an overly careful adaptation that diminishes the production’s theatricality.

There is a ready-made audience for Nottingham Playhouse and Liverpool Everyman and Playhouse’s touring production. The success of both Khaled Hosseini’s original book and the subsequent film means that many people are already familiar with the story, which ranges over two continents and spans nearly thirty years.

Amir, the son of a successful businessman in 1970s Afghanistan, has a close relationship with Hassan, the son of Amir’s father’s servant and a member of the Hazara minority. Hassan is the ‘kite runner’ of the title – someone who chases after fallen kites that have been defeated in Kabul’s kite-fighting contests. However, Amir fails to protect Hassan from a vicious sexual assault, a betrayal that haunts Amir until many years later he finds there may be ‘a way to be good again’.

Adaptor Matthew Spangler seems determined to satisfy fans of the book by including as much of it on stage as is physically possible. Unfortunately, such determination means that Amir spends huge sections of the piece acting as a narrator. This is doubly difficult, as the character’s journey towards redemption depends on his being a thoroughly dislikeable figure for much of the play.

Ben Turner makes a monumental effort as Amir, and shows the character at different ages convincingly. However, the swathes of exposition weigh down the narrative significantly and diminish the dramatic effect.

One of the most touching moments of the play, between Amir and his seriously ill father Baba (the excellent Emilio Doorgasingh) is undercut by the adaptor’s insistence on telling us what we have just seen and its significance. Similarly, one of the plot’s big revelations towards the end is followed by Amir telling us how it sheds light on what happened earlier, when anyone paying the slightest attention would be able to work it out for themselves.

let the drama speak for itself

There seems to be a reluctance to let the drama speak for itself, instead anchoring it too firmly to the book in a way that does neither any favours. What is doubly frustrating is how well the production struggles to rise above these limitations. Barney George’s elegant and simple set, William Simpson’s projections and Hanif Khan’s live tabla playing add delicacy. Giles Croft’s direction, particularly in the kite-flying sequences, shows how much more effective the production would be if it showed more and told less.

As it is, the insistence on leading the audience by the nose means that the second act becomes far too long, which only serves to point out some of the more obvious coincidences in the plot. Too often, the narrator goes through a sequence of events and dates while the other members of the cast are sidelined.

When there is interplay between the performers, the production becomes much more fluent and involving. Anthony Bunsee’s General Taheri is a touching study of a man in exile trying to cling on to his identity in a strange country. Nicholas Karimi, as the psychotic Assef, manages to make the character chilling without lapsing into melodrama. Andrei Costin, who plays both Hassan and Hassan’s son Sohrab, conveys both the innocence of childhood and traumatic despair in a suitably heartbreaking fashion.

The emotional involvement and dramatic drive these performances bring to the story makes it all the more disheartening that the prosaic nature of so much of the adaptation weighs it down. Relationships between fathers and children are explored, moments of guilt, sin and redemption are shown – and then the play comes back down to earth with a bump as we have to be told what the narrator thinks of it all.

As a book put on stage, this is largely successful, and will surely not disappoint fans of the original work. As a dramatic performance in its own right, it is much more problematic.

Running time 2 hours 55 minutes including interval

King’s Theatre, 2 Leven Street EH3 9LQ

Monday 10 – Saturday 15 November 2014

Evenings 7:30pm; Matinees Wed and Sat 2:30pm

Tickets from http://www.edtheatres.com/kiterunner

The novel, film and playscript are available through Amazon. Click on the images for details:

ENDS