The James Plays

The James Plays Trilogy: ★★★★☆

Festival Theatre: Wed 3 – Sat 13 Feb 2016 then on tour

Review by Hugh Simpson

Eighteen months after their first outing, the National Theatre of Scotland’s production of the James Plays trilogy remains a theatrical event worth anybody’s time and money.

They are still on a massive scale, superbly staged and wonderfully acted.

With the dust now having settled, it seems that some of the brouhaha from last time may have been a little out of proportion – putting a review stating ‘better than Shakespeare’ on your posters is really asking for trouble.

These three history plays about the 15th century Stewart kings of Scotland remain a real achievement taken as a whole. Individually, what we have is one play approaching greatness, one that is tremendous fun, and one that still does not quite work.

James I appears to be the one that could be most easily understood or assimilated on its own, and the one that looks most likely to have a life apart from the trilogy. It is easy to imagine productions of it by companies lacking the resources, time or inclination to mount the full trilogy; it is difficult to imagine the other two working in isolation.

It is certainly the most traditionally structured of the three plays. Even if the events depicted happened years apart in reality, they follow on from each other seamlessly, and the narrative hangs together beautifully.

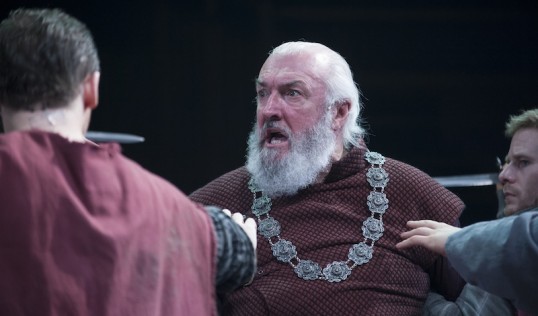

This is helped, as in all three plays, by having some very fine individual performances contained within the remarkable 20-strong ensemble. Steven Miller’s James I is a thoughtful, sympathetic portrayal, depicting the character’s struggles to impose his rule on the country while maintaining his own principles.

momentum

Rosemary Boyle’s Joan, the seventeen-year-old English wife of James, is a similarly effective performance. Boyle makes the character’s transformation entirely believable – something that cannot necessarily be said of her peculiar turn as Mary of Guelders in the second play.

Two performances gain considerable momentum across the first two plays – the initial fire and energy of Sally Reid’s lady-in-waiting Meg is opened out into a rounded and entirely successful performance, while the monstrous transformation of Balvenie (Peter Forbes) is very well done.

James II was widely regarded first time round as the weakest part of the trilogy, and little seems to have changed. Alterations have been made to Rona Munro’s script and Laurie Sansom’s direction, but the underlying problems still remain.

The nightmarish elements in the opening sequences have been toned down, and a more realistic approach substituted. Unfortunately, this removes much of what made this play stand apart from the others, while doing little to remedy the unfocused nature of the narrative.

The relatively unsuccessful nature of this central third is in no way down to the acting. Andrew Rothney’s James II is a performance of real drive and commitment – it is significant that when he injured himself during the performance, the first inkling that a huge proportion of the audience had of it was when he had to be helped offstage at the curtain call. His scenes with Blythe Duff, who is tremendous across all three plays, are among the very best parts of the whole trilogy.

rollicking

Andrew Still brings a swagger and fury to the king’s dangerous friend William Douglas, but the focus on their relationship, following on from a first half that leaps about in time, leads to a structure that is too diffuse and lopsided to work completely.

Very definitely set apart from the first two parts in its rollicking, anachronistic, ‘throw the kitchen sink at it’ style of direction, James III is still great fun but perhaps loses something on a second look.

The production relies a little too much on theatrical stunts and humour that do not bear repeated viewing. The ‘state of the nation’ parts in the second act, shorn of the proximity to the referendum that gave them an electrifying power for many last time round, are a little out of place. They now sound vague and generalised, and even a little trite.

Once again, this is not down to the acting. Queen Margaret is really the play’s central figure, and is here played by the Swede Malin Crepin. At first she struggles a little with the demands of a role in an unfamiliar language but grows into a performance of poise and charm.

Matthew Pidgeon’s James III loses much of the sulkily adolescent wannabe rockstar pose Jamie Sives brought to the role, but instead has a fiery, dangerously magnetic intensity.

scale and ambition

Interestingly, the alternative titles of the plays seemed to have been downplayed – there is no mention of them in the programme, for example. The mirror mentioned in the third play’s subtitle The True Mirror, and prominent onstage, remains an interesting device, and provokes questions of how theatre reflects the ‘truth’ of history and society, and of how Scotland sees itself – but these are left hanging, and never really integrated into the narrative, as if nobody really knew what to do with them.

This revival, rather than showing anything new about the plays or the production, confirms many previous opinions. The sheer scale and ambition of the whole production is breathtaking. The fluidity, variation and confidence of Laurie Sansom’s direction is still remarkable.

The ensemble deserve the highest praise. Half of the original cast have been replaced, but the standard remains remarkably high; the strength of the ensemble is demonstrated by the way David Mara, deputising for the injured Rothney in the last play ‘on the book’, was integrated smoothly into the whole. Jon Bausor’s set is a thing of awe and wonder, while music, sound, movement and fighting are cleverly used.

However, the odd drawback that was noticeable before is magnified by the revival. The lazy jokes about Scotland’s weather, size or diet are still far too frequent; the Caledonian cultural cringe embodied by Scottish audiences laughing dutifully at them despite any semblance of wit or originality remains dispiriting.

This is a minor quibble, but there is a deeper problem with the plays’ language which means that the ‘whaur’s yer Wullie Shakespeare noo?’ reaction from 2014 (led, interestingly, mainly by London-based critics, with Scottish voices being more circumspect) is just hyperbole.

watered down

There is no problem whatsoever with the swearing, or the use of a modern, demotic Scots – albeit one that seems a little watered down for the benefit of other audiences. On the contrary, playwright Rona Munro has proved in the past to be an expert at crafting pure poetry from exactly such a language.

This does not happen here. Over the three plays the language remains strangely flat, with few moments of poetic grandeur. There is no hiding away from comparisons with Shakespeare – by making one of the first characters to speak on stage Henry V of England, Munro practically invites the comparison.

In the end, the idea that history is best expressed by showing What Kings Did may have been the way to go 400 years ago, but does not really work now, and Munro is aware of this. It is notable that one of the scenes that most approaches the grandeur and reach some want to attribute to the trilogy comes in the first play, and features the characters of Queen Joan, Meg and Isabella (the superb Duff again). That such power comes from three female characters shows there is another way of doing history plays – further confirmed by Margaret’s role in III – but this is not carried through significantly.

Comparisons with David Greig’s Dunsinane – another recent Scottish work that demanded comparisons with Shakespeare, being effectively a sequel to Macbeth – are unfair but unavoidable. Greig’s play succeeds in touching Shakespearean heights of folly and epic grandeur on occasion; it also seems to get better with repeated viewings. Revisiting The James Plays suggests this is true of James I but not of the other two.

But in the end, this determines only whether the cycle is a great achievement or a very good one. Taken cumulatively, the trilogy is unreservedly recommended, particularly if watched in one go if possible. There are theatrical memories to be treasured for many years here, and there may never be another chance to see it all again – grab this one while you can.

The James Plays

Festival Theatre 13/29 Nicolson Street EH8 9FT. Phone booking: 0131 529 6000

Wednesday 3 – Saturday 13 February 2016

James I: ★★★★☆

Running time: 2 hours 35 minutes (including one interval)

Wed 3: 7.30pm; Sat 6: 12pm, Wed 10: 7.30pm; Thu 11: 2.30pm; Sat 13 at 12pm.

James II: ★★★☆☆

Running time: 2 hours 25 minutes (including one interval)

Thu 4: 7.30pm; Sat 6: 4pm; Thu 11: 7.30pm; Sat 13: 4pm.

James III: ★★★★☆

Running time: 2 hours 35 minutes (including one interval)

Fri 5: 7.30pm; Sat 6: 8.15pm; Fri 12: 7.30pm; Sat 13: 8.15pm.

Hugh’s reviews of the original production can be found here: tag/the-james-plays

| The James Plays on tour 2016: | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Wed 3 – Sat 13 Feb | Edinburgh Festival Theatre |

0131 529 6000 | Book online |

| Fri 26 Feb – Tue 1 Mar | Adelaide Festival Theatre |

00 61 131 246 | Book online |

| Sat 5 – Sat 12 Mar | Auckland ASB Theatre |

0800 111 999 | Book online |

| Wed 30 Mar – Sat 2 April | Inverness Eden Court |

01463 234 234 | Book online |

| Fri 8 – Sun 10 April | Glasgow King’s Theatre |

0844 871 7648 | Book online |

| Sat 16 – Sun 17 April | Northampton Derngate |

01604 624 811 | Book online |

| Sat 23 – Sun 24 April | Salford The Lowry |

0870 787 5780 | Book online |

| Sat 30 Apr – Sun 1 May | Newcastle Theatre Royal |

08448 11 21 21 | Book online |

| Sat 7 – Sun 8 May | Sheffield Lyceum |

0114 249 6000 | Book online |

| Sat 14 – Sun 15 May | Norwich Theatre Royal |

01603 63 00 00 | Book online |

| Fri 20- Sat 21 May | Canterbury Marlowe Theatre |

01227 787787 | Book online |

| Sat 28 – Sun 29 May | Plymouth Theatre Royal |

01752 267222 | Book online |

| Sat 11 – Sun 12 June | Nottingham Theatre Royal |

0115 989 5555 | Book online |

| Thur 16 – Sun 26 June | Toronto Luminato Festival |

416 368 4849 | Book online |

ENDS

Comments (3)

Trackback URL | Comments RSS Feed

Sites That Link to this Post